Facing the Past: Cambodia Then and Now

by William Dunlap and Linda Burgess

In Looking for the Buckhead Boys, the late American poet James Dickey describes the trauma of confronting his old high school annual as tantamount to staring into the Book of the Dead.

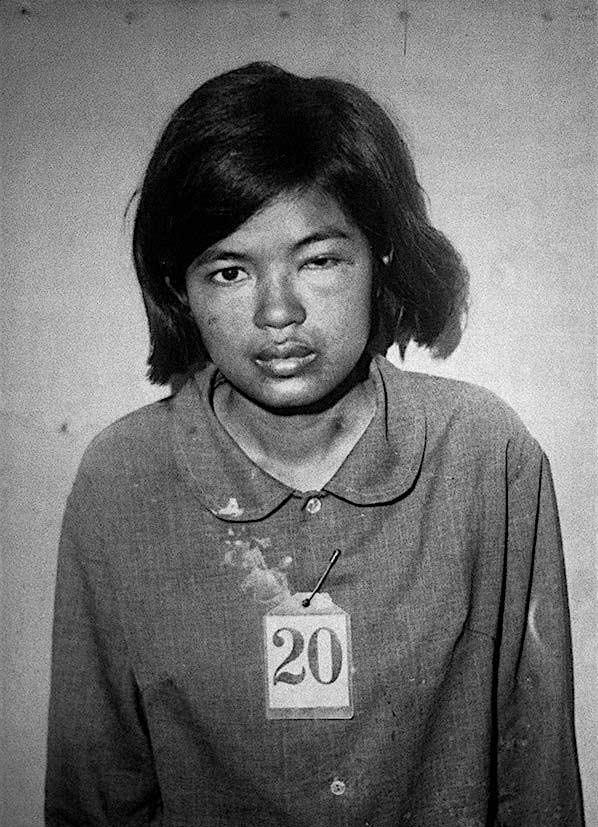

We are looking at just such a book. It is the right size, gray cloth bound with an embossed gloss black square on the front and back cover. Inside are 78 exquisite and haunting images made during a 3 year, 8 month, 20 day period inside a former high school in the suburbs of Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Each photograph is elegantly printed full page on Japanese paper by sheet-fed gravure process. They are anonymous portraits of young and old by an anonymous photographer. Dark eyes stare back from these pages, either into or out of oblivion. It's impossible to know which. On the spine of this handsome book is its title, The Killing Fields.

The instigator of these photographs was himself a former teacher turned Maoist revolutionary and, in time, pathological murderer of some 2,000,000 of his fellow countrymen. Saloth Sar, aka Pol Pot, came to power in April 1975. He had been the paranoid and demented Secretary General of the Communist Party of Cambodia. As Brother Number One he renamed his country Democratic Kampuchea and ruled it without compassion. His Khmer Rouge forces systematically evacuated the cities, abolished schools, markets and currency, outlawed religion, collectivized agriculture and industry, turned the calendar back to 0, and effectively ended 2000 years of history. He also turned Tuol Sleng High School, code named S-21, into the most notorious of Cambodia's numerous detention and low-tech extermination camps. Enemies of Angkar were brought here, interviewed and photographed, then tortured to extract meticulously hand-written confessions. Afterwards, these betrayers of the revolution were trucked to the Choeung Ek killing field where their final earthly act was to dig their own shallow graves before being bludgeoned to death.

Some 17,000 souls matriculated through these halls of de-education. This is their annual, their yearbook, their Book of the Dead.

The publication of The Killing Fields, (Twin Palms Publishers, $50. hard bound) is the culmination of the tireless efforts and brilliant insight of its two editors, American photographers Christopher Riley and Douglas Niven.

In March of 1993, while freelancing for Agence France-Presse, the Phnom Penh Post and others, these intrepid journalists stumbled across a cache of some 6000 dusty and deteriorating negatives in a Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide file cabinet. Jarred by the visual impact of these images and fascinated by their find, Chris and Doug established the Photo Archive Group for the sole purpose of preserving this unique photographic record of Cambodia's most recent political and cultural nightmare. Their first order of business was to clean and catalogue the negatives, and make contact prints to aid in the identification of S-21 victims. Next, some 100 images were selected for archival printing, publication and exhibition.

One of the more difficult tasks lay in securing permission from the Cambodian Ministry of Culture for all of the above, and raising funds to support the project. All this was accomplished, as well as setting up a sophisticated darkroom on site, getting loads of world wide publicity, finding a first-rate publisher, producing and editing the book while scheduling a slew of museum venues, one of which is an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, May 15 through August 15.

In the meantime, the Photo Archive Group has identified four more bodies of photographic material at risk and in need of rescue. They have also tracked down and interviewed Nhem Ein, one of Tuol Sleng's here-to-fore anonymous Khmer Rouge photographers. Not bad for a couple of young Californians who could have been surfing.

We first met Doug Niven in the fall of 1994 at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Thailand, high atop Bangkok's Dusit Thani Hotel. He was addressing a crowd gathered under the auspices of the Indochina Media Memorial Foundation for an exhibition of work by photographers who had, since 1945, covered the perpetual state of conflict in southeast Asia. The IMMF, which British photojournalist Tim Page helped found in 1991 to pay homage to the 320 journalists who have died or disappeared in Indochina, also supports and promotes projects by current members of the profession working in the region.

The exhibition, entitled "War, Peace and the Printed Image Revisited," was full of the kind of images that made one glad to have postponed any visit to Indochina until after the smoke cleared, the dust settled, and the blood dried. Most of the photographs in this annual exhibition were familiar. Many were famous, like Nick Ut's indelible image of 9 year old Kim Phoc running naked from a napalm attack in Trang Bang, Vietnam circa 1972. But there, among the works of Sean Flynn, Horst Faas, Lance Woodruff, Tim Page and others, was something ever so different by a photographer listed as "Unknown." A mesmerizing group of full face mug shots in frighteningly fine focus, some of the negatives distressed, each titled "Tuol Sleng Prisoner - Cambodia - 1975-79." This was our initial exposure to the visual legacy of the Khmer Rouge.

Doug Niven spoke with passion and eloquence about the Tuol Sleng Project and the general conditions of life in Cambodia, while there on the wall just behind him, over his shoulder were these faces, timeless and mysterious, staring back and speaking volumes for themselves. At that moment these photographs were doing something that is absolutely crucial and necessary if an object is to transform itself into an artifact. They were transcending their original time, place and function, and becoming, to our western eyes and consciousness, significant works of art.

The following month we caught up with Doug in Phnom Penh while en route to Siem Reap and the Temples of Angkor Wat. Our decision to travel to Cambodia had not been without trepidation. The week before our scheduled departure there were reports that the executed remains of three western backpackers, kidnapped and held for ransom by Khmer Rouge forces, had been found. France, Great Britain and Australia warned their citizens against traveling to Cambodia, as did Cambodia's own King Sihanouk and every English language paper one picked up. We called the American Embassy in Bangkok and spoke to the Regional Security Officer. He assured us that flying within Cambodia presented no problem though cautioned against any over land travel. Still we were hesitant. Then one morning on CNN we heard there had been a hung jury in the case of a British tourist murdered near Tallahassee, Florida. The newscaster tagged the report, saying, "So far this year, nine foreign tourists have been murdered in Florida." Florida nine, Cambodia three. Two days later we flew to Phnom Penh.

Cambodia ChildAt Doug's insistence we visited Tuol Sleng, now a Museum of Genocide created by the Vietnamese before they pulled out of Cambodia in 1989. It was closed that day, but our ever resourceful guide, Mr. Cheng, talked us in and we had the sad place to ourselves. The U-shaped compound looked like so many institutional buildings in tropical climes: louvered shutters on the windows, broad patterned tile floors, thick white-washed walls marked with the kind of grafitti you might find at any high school anywhere. Remnants of math problems were still scribbled on blackboards. In contrast to all this was evidence of the horror that had happened here: classrooms rigged for torture and detention, metal beds equipped with shackles, fetters, chains. Photographs of those tortured papered the walls. Human skulls had been fashioned into a map of Cambodia to chart the genocide. Discarded busts and portraits of Pol Pot lay piled in a corner, and the 19th century photographer's posing chair, itself looked for all the world like an instrument of intimidation.

It was as chilling and sobering an experience as could be imagined. That is, until we drove the 10 miles out of the city into the beautiful pacific countryside, the same route taken by the condemned of Tuol Sleng. The first notion you get that you are entering sacred ground comes at the sight of a tall tower rising some three stories above this ethereal landscape. It appears to be a typical Buddhist chedi until you realize that it is literally filled with human skulls from top to bottom. Brahma cattle grazed in the surrounding pasture and drank from the many small pits which dot the landscape like so many bomb craters. They were made by the excavation of mass graves. The ground continues to cough up human remains: bone chards, scraps of cloth, pieces of knotted rope...

Of the thousands of Cambodians "processed" through S-21 only seven are known to have survived. Vann Nath was 31 years old with a wife and two children when he was taken to Tuol Sleng Prison in December of 1977. Before the revolution he'd worked as a commerical artist, but more recently he'd been chopping wood and building dams in a labor camp. After a month of torture, interrogation and starvation at the hands of his captors, he was summoned before the chief of the prison. Shown a large photograph of Pol Pot, he was asked if he could paint an exact reproduction. By accident of his avocation, Vann Nath was spared to serve the Khmer Rouge propaganda machine. He would spend the duration of his incarceration, eleven more months, painting and sculpting likenesses of Pol Pot. The whole of Vann Nath's moving story is related by Sara Colm in The Killing Fields.

Everyone in Cambodia seems to have a story. As we wandered around the network of open graves, our guide Cheng spoke impassively about the Khmer Rouge reign of terror. He pried a human bone from the earth as he told how 19 members of his family had perished. Only he and his father lived through it. Then he smiled and picked up a ripe palm fruit, opened it and offered us some. Its flesh was juicy, aromatic and sweet, but with a bitter after taste that lingered.

The annual Water Festival is a huge celebration which draws thousands of people in from the provinces. It was in full swing when we returned to Phnom Penh. The Mekong River teemed with colorful boats, its banks were crowded with costumed revelers. The aroma from food stalls, and sounds of vendors and loud music permeated this carnival atmosphere. The Khmer Rouge had of course threatened to disrupt the festivities so military patrols were in evidence everywhere. This general frivolity played hard against the somber reality of our experiences earlier that day. But there was such an over arching sense of joy in the air that it was difficult not to be won over.

Inside the National Museum where many priceless Khmer treasures reside, statues of dieties were in worship. The crowds prayed to and stroked the sculptures. They draped them with saffron fabric and brought flowers, burning candles and incense as offerings. Some of these same works of art are part of the "Sculpture of Angkor and Ancient Cambodia: Millienium of Glory," at Washington's National Gallery of Art, June 29 through September 28, 1997. Our western notion of detached observation was entirely foreign to these gentle people, whose ancestors carved the sculptures and built the temples.

We left the next morning for Siem Reap, the colonial city at the edge of the 100 square mile complex of temples and jungle generically called Angkor Wat. Everyone on our Air Kampuchea flight was more deferential than usual given that Prince Norodom Ranarridh and family were on board. We all deplaned to the strains of a military band and armed escort. One can get used to that sort of thing.

Doug Niven had told us that David Chandler, the famous scholar of Cambodian history, would by chance be in Siem Reap and staying at our same hotel. Not so much by chance, given that the Grand Hotel was then one of the few places one could stay. Professor Chandler had agreed to write an essay for the book and was using his considerable influence to push the Tuol Sleng Project along. We checked in and left Chandler a note on a business card, and headed immediately for Angkor Wat and environs, where we remained for the day -- stunned, stupefied, speechless and generally overwhelmed by the architectural achievements of ancient Khmer civilization.

David Chandler, an American teaching in Australia, is generally considered to be the definitive authority on all things Cambodian, to which his impressive body of published works will testify. We met him for a drink that evening at the bar of the Grand Hotel. The sounds of the ubiquitous water festivital were audible inside this once glorious but now ruined mansion. It hadn't seen much paint since Jacqueline Kennedy stayed there as King Norodom Sihanouk's guest in 1967.

Cambodia ChildWe introduced ourselves, exchanged pleasantries and then, holding up the card we'd left with our McLean, Virginia address, he asked, "Are you CIA?" Our laughter was interrupted by a series of loud, sequential noises. A sharp pop, pop, followed by a burst of them. The young lady who just delivered our drinks hit the floor. The man and woman behind the desk ducked. We looked at each other as the hotel staff, who'd been ducking and dodging for decades, slowly emerged and peered cautiously out the front door into the late afternoon light. David Chandler took a long drink from his beer and said, "Fireworks. Now, what can I do for you?"

What David Chandler did for us, and what he does for this book in his essay "The Pathology of Terror in Pol Pot's Cambodia," is supply a historical narrative that gives context, since no rational explanation is possible, to the events in Cambodia that led inevitably to the killing fields. His spare and powerful language is authoritative but never didactic, informative without being condescending. These pictures need little text, and Chandler's essay and Vann Nath's survival memoirs are just enough.

We talked at length that evening in Siem Reap about the Photo Archive Project, Pol Pot, Tuol Sleng, Angkor Wat and what it all meant. When asked how a predominantly Buddhist, apparently passive population could turn on itself in such a suicidal manner, he said with a historian's sense of resignation that the recent grisly events were not an anomaly. For precedent we'd but to look closely at the story told by the bas-relief walls of Bayon when we returned to the temple complex on the morrow. Later, reading his book The Tragedy of Cambodian History, we learned that in Cambodian, the phrase "to rule" translates as "to devour."

It is useful to remember that Pol Pot, despite recent high level defections, survives, even thrives on the border between Cambodia and Thailand, where he controls several provinces. The Khmer Rouge continue to engage in politcal and criminal activites. Their main source of income is the smuggling of contraband: teak, drugs and antiquities, with the occasional kidnapping and assassination thrown in for good measure.

Ironically, it is this looting of the treasures of Angkor that most threatens its existence, for it has otherwise been remarkably untouched by the decades of war. The obscure and difficult to reach sites are especially imperiled but even the more visited temples are not immune. The looters are organized, resourceful and bold. Huge stones weighing tons have been known to disappear overnight and armed raids on the conservation depot in Siem Reap are not unheard of. All to satisfy the insatiable appetite of the international market for Khmer objects, whose center is in Bangkok.

A recent publication by the International Council of Museums, "100 Missing Objects: Looting in Angkor," has had encouraging results. Several sculptures were returned to Cambodia this spring from public and private collections in the west, including the Metropolitan Museum in New York City.

The appeal of these carved effigies is obvious, as anyone who has seen the "Sculpture of Angkor and Ancient Cambodia," in either Paris or Washington can testify. But as marvelous as these works look in their clean, well-lighted, climate controlled, contemporary museum spaces, the effect on one strolling the cleared paths at the temple Ta Prohm and witnessing the unintentional collaboration of man and nature is one of the more incomparable experiences of a lifetime. Giant ficus, banyan and kapok trees canopy this majestic site and their exposed system of roots, which initially tore apart walls and chambers, now hold individual figures, heads and the entire structure together like so many living buttresses. Some conservationists wisely want to preserve this delicate balance and are as protective of these trees as they are of the stones.

Most of the pieces in the "Millennium of Glory" exhibit at the National Gallery of Art were borrowed from either the Musée national des Arts asiatiques-Guimet in Paris or the National Museum of Cambodia in Phnom Penh. Made between the 6th and 16th centuries, the works reflect the cultural confluence of both Hindu and Buddhist traditions. The gods, dancers, mythological creatures, and legendary guardians gathered each have an eerie presence, made all the more profound by the sheer force of their numbers. They possess a spiritual dignity and deftness of execution despite their often fragmented and damaged condition. Stone, bronze and wood seem to almost live and breath, which can no longer be said for the poor souls who faced the camera lens in The Killing Fields. They live only in the dimming memory of family and friends, and in that fraction of a second of exposure on celluloid which has thrust them into that nebulous timelessness called art.

Copyright 2003 William Dunlap. All rights reserved.